Alex Caruso was recently asked how many NBA players could lead a 16-seed to win March Madness. He answered 27, which basically means every All-Star.

Alex Caruso played four years in college, including a run to the Sweet Sixteen, and has played with a number of All-Stars in his NBA career including Shai Gilgeous-Alexander and Jalen Williams this year, as well as LeBron James, Anthony Davis, Brandon Ingram, Julius Randle, DeMar DeRozan, and Zach LaVine. So I trust he knows what he’s talking about.

But still, could 27 different NBA players1, many of whom are just a handful of years removed from college themselves, lead a bunch of below average hypothetical teammates against Cooper Flagg, Dylan Harper, Ace Bailey, and other top prospects who will be playing in the NBA later this year?

Do NBA players really get that much better after college?

MVPs: Just Keep Swimming

The MVP frontrunners this year, according to Basketball Reference and literally everyone else, are Nikola Jokić and Shai Gilgeous-Alexander. But I don’t want to talk about the incredible things these guys are doing this year. Instead I’m asking, “What took you so long to get so good?”

I know, I know. I sound like the reporter2 asking Steph why he only has 11 All-Star selections.

Nevertheless it is interesting that both these guys flew under the radar for a few years before emerging as the best of the best:

Shai was selected 11th by the Hornets in 2018, traded on draft night, then traded again after one ok year with the Clippers.

Jokić was famously drafted during a Taco Bell commercial, 41st overall in 2014, and didn’t make an All-Star team until year 4.

Let’s throw Giannis Antetokounmpo in the mix as well, who is penciled in as the (distant) third in this year’s MVP race. Maybe the most unguardable player in the league these days, Giannis was similarly overlooked as a skinny 19-year-old and fell to pick #15 in the 2013 draft.

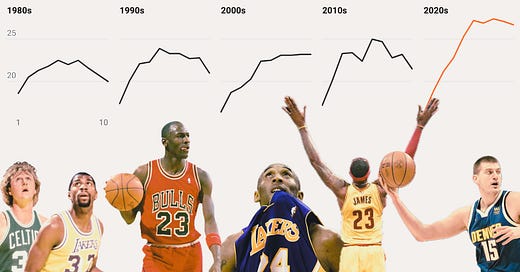

Alright, time for some charts. Here’s how those three players got to the top of the NBA3:

Shai and Giannis each started below average and steadily worked their way up to their current MVP-level performance. After playing professionally in Europe for a year, Jokić started slightly higher but has also seen a steady upward trajectory, peaking (so far) after 7 years.

Of course NBA players develop their skills while they are playing in the NBA - that’s what player development coaches are for. And there’s also the natural progression that comes with age and experience. But it’s the prolonged duration of improvement that I find so impressive. These guys are some of the best examples of steady hard work paying off, but they are actually indicative of a larger trend in development arcs that has been going on in the NBA for nearly half a century.

Two things stand out:

The eventual best players are starting slower than they used to. In the 1980s, the best players produced immediately, hitting, on average, 75% of their future realized PER in their very first year in the league. No future top 5 player has hit that mark since rookie Chris Paul in 2008. As a whole, today’s stars started their careers barely above average as a group (16.2 PER vs league-wide average of 15).

Today’s best are doing things we haven’t seen in over half a century. All-NBA level players are averaging PERs around 27 lately, which is best-ever level. Only Jokić and Michael Jordan have averaged 27+ for their careers. 4 of the top 5 PER seasons of all time have come this decade4 (Jokić 2x and Giannis 2x). Shai is on pace for the second highest PER season ever by a guard5.

I’m not getting into debating generations (for now), but it is crystal clear that today’s elite have made more progress after getting into the NBA than their predecessors.

So what’s changed? I won’t claim to have all the answers, but I will offer a few thoughts:

Player development coaches. In Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s last season in Milwaukee, the Bucks had just one assistant coach. Today, Giannis’s team has 10. And that doesn’t count the dozens of analysts feeding the players information on how to further optimize their game. Giannis got rid of threes this year. Jokić has taken more. Shai learned how to get to the free throw line even more. All of this support around key changes have allowed them to keep getting better, year after year after year.

The NBA has more talent than ever before. The more frequently cited commonality among this triumvirate is their international background. Giannis is from Greece 🇬🇷, Jokić is from Serbia 🇷🇸, and Shai is from Canada 🇨🇦. The game has grown so much and the league can now pluck stars from a much larger pool than in the Dream Team days. Young, raw talent could compete in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but it’s a lot harder in today’s NBA.

Players come to the NBA with less experience than they used to. Larry Bird played his first season at 23. Kareem entered the NBA at 22 after 4 years (and 3 National Championships) at UCLA. David Robinson was a 24-year-old rookie after completing his military service. They were ready to go up against the grown men in the NBA. Shai and Jokić were just 20 in their first NBA seasons, and Giannis just 19.

On this last point, the exceptions help to prove the rule. In the 2000s, teenagers like Kobe Bryant, Kevin Garnett, and Jermaine O’Neill were allowed to join the league fresh out of high school. As good as they were and would be, they needed a few years to get their feet under them, as seen in the dip in starting PER that decade.

Of course, there are always some exceptions that prove … the exception. Here are some more interesting careers to consider6:

MIPs: Don’t Look Back

What about the flip side of this slow and steady, 1% better everyday, mindset? Guys who come out of nowhere with a HUGE season. I assumed they would go back to their normal selves (regression to the mean and all), and so the top guys would avoid these big jump seasons.

But that’s not the case. Giannis actually won the Most Improved Player (MIP) award in 2017, with a near 30% jump in PER from 2016. Of course, Giannis kept making big strides as described above. But I was surprised to learn that most MIPs actually don’t regress to the mean very much.

Let’s start with what a typical MIP career progression looks like by PER. Here’s 2024 MIP Lauri Markkanen’s career so far:

As you might expect, the typical MIP starts their career pretty flat, before having the breakout. But then, we don’t really see a hard regression to prior performance with these players. Sure they drop off a bit, but they are still almost always better than their pre-MIP season selves.

Generationally, the pattern has stayed the same since the award was first given out in 1985. MIPs are slightly better now then they were in prior decades (both before and after their MIP seasons)7, but the shape of progression remains roughly the same.

Of course, the aggregate hides interesting career stories. Here’s some highlights:

A few thoughts:

Kevin Love (not Ja Morant) was the “best” player to win MIP before winning it

Julius Randle was the rare MIP to regress to below average the following year. He’s since bounced back, then back down, back up, …

Jimmy Butler won MIP? I forgot about that

Hedo Türkoğlu was named MIP in his 8th season, the latest late bloomer

Monta Ellis and Jermaine O’Neal had bigger jumps the year after winning MIP than in their MIP-winning year

Boris Diaw had the largest PER % increase in a MIP-winning season, at 73%

Zach Randolph won MIP despite his PER falling from the previous year. He did double his minutes and his counting stats rose accordingly

Other than Giannis, Tracy McGrady hit the highest career peak PER of any MIP

Isaac Austin won MIP in his first year back from playing in Turkey for a couple seasons

Overall, most of these players had / are having really good careers, and they’ve had most of their success after winning MIP. Sure that makes sense on one hand, but I wouldn’t have been shocked to see more players I’d never heard of on this list. One-hit wonders ala Dexy’s Midnight Runners.

In summary, if you want to be a really good NBA player, just keep getting a little better each year. Or get a lot better one year and stay that good. Easy. More teams should do this.8

Stay tuned next week when I’ll do a similar look into the WNBA. I suspect the outcomes will be pretty different.

The 27th best is, coincidentally, Caruso’s teammate Jalen Williams according to the Ringer’s current rankings.

I’m still working on the Aussie accent.

As measured by Player Efficiency Rating, or PER, an advanced stat that gives a “per-minute rating” of a player's performance. It accounts for all the things you want it to: points, rebounds, assists, field goals, threes, steals, blocks, etc. etc.

The 5th is, unsurprisingly, Wilt Chamberlain in 1961-62.

Only behind Steph Curry’s 2015-16 season.

As a side note, maybe Victor Wembanyama will be a return to the past in this regard. He posted a 23.1 PER in his age-20 rookie year, the 4th best start amongst this group of future top 5 MVP finishers (I think it’s fair to assume Wemby will join this list). The other three are David Robinson, Michael Jordan, and Dr. Julius Erving.

That is partly because MIPs win the award later in their careers on average now vs in prior decades.

Yes, the title is a reference to Monty Python.

Oh my goodness this is my fricking love language!!!!! I’m so hyped about diving into your content!!!

Absolutely killer work here Chris